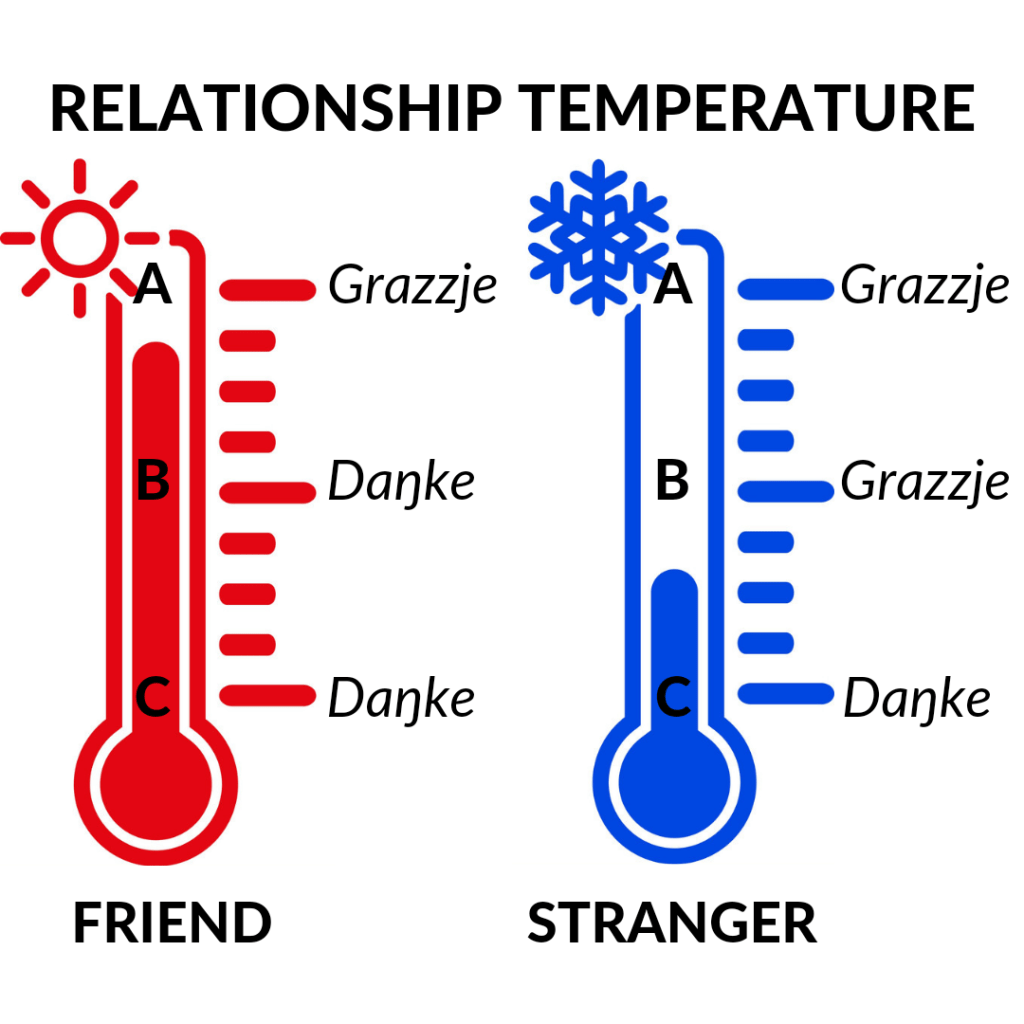

B: Hosting you at their home (ordinary for a friend, extraordinary for a stranger)

C: Giving you directions (ordinary for both)

Keep in mind that the values of A, B and C are not absolute, but relative: if the stranger is your bodyguard, A is much lower. A in this case is ordinary even if your relational temperature is low.

If you are a Human, you know that you owe things to others and others owe things to you.

The Italian saying Niente è dovuto a nessuno (“Nothing is owed to anyone”) doesn’t make any sense from our point of view: society works because people owe things to one another. Not to friends only, but to strangers, foreigners and enemies too. Only the worst enemies don’t owe anything to each other.

What is owed and what is not is not determined by liking, sympathy or privilege, but by the key concept to understand how the Human society works, relational temperature.

Between you and every other person (your partner, a relative, a friend, a colleague, a neighbour, a stranger…) there is a peculiar relational temperature, known to both of you through a process – soon explained – grounded on past experience.

The higher the relational temperature, the more you owe to each other, the lower the less.

The temperature shows the level of trust, not the level of liking: it may be high even if you dislike each other or it may be low even if you like each other. Since this temperature can be increased or decreased as you want, feelings have certainly a role in it, but Human relations work more on obligations than on feelings. Not because feelings are not important to us, but, on the contrary, because your short-term feelings may hurt the other’s long-term ones, while your obligations will foster them.

For this reason Foreigners look whimsical to Humans: if they stop liking you for any or no reason at all you become a stranger to them, whatever your past experience.

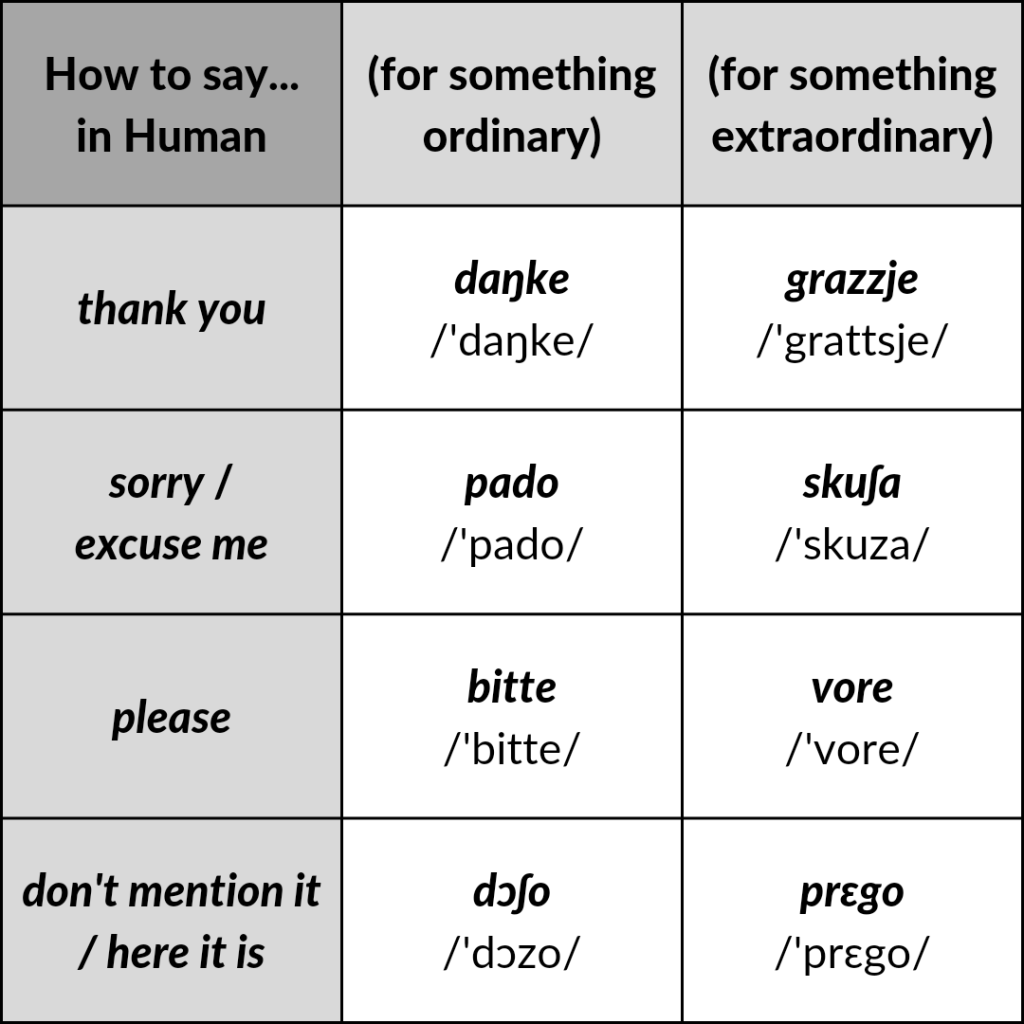

The relationship temperature is known to both of you through eight temperature words that are used as an index of it. In English they are known as “magic words” and are “thank you”, “sorry/excuse me”, “please” and “don’t mention it/here it is”.

These words are common to almost all languages. The difference is that only Human makes a distinction between ordinary (within what is due) and extraordinary (beyond what is due) thank yous, sorrys and so on, in order to make clear what is the relational temperature.

If you say daŋke, you show that you are thanking for something that you consider normal in your good and working relationship (whose temperature is above that). If you say grazzje you show that you did not expect that, that it wasn’t implied in your relationship (whose temperature is below that) and that you are now in debt to him. The other can reply dɔʃo, if he wants to make you know that the relational temperature is above that, or prɛgo if below. Replying dɔʃo to a grazzje is the most common way to raise the relational temperature, prɛgo to a daŋke to lower it.

The same applies to pado (“I am apologizing for something you have to accept, because of our good terms”) and skuʃa (“I am apologizing for something you may not accept”) and to bitte (“I am asking for something you have to do, because of our good terms”) and vore (“I am asking for something you may not do”), whose replies can be dɔʃo or prɛgo (or no, if you do not accept).

Dɔʃo and prɛgo can also be used by themselves, with the meaning of “here it is”: dɔʃo means that you are not expected to refuse it, prɛgo that you can. The other, if he accepts, replies with daŋke or grazzje (that won’t need a dɔʃo o prɛgo as a reply).

A series of focuses and examples will explain in depth the mechanisms of temperature words, but three key concepts to keep in mind are these:

- You are not supposed to show a higher temperature than the real one (which is instead polite in some Foreign cultures): otherwise you will be looked as phoney.

- You can change the relational temperature as you like, but you have to avoid excessive temperature swings and refusing things below the current temperature (accept them and reply prɛgo, instead): otherwise you will be looked as fickle-minded.

- You have to confirm any temperature rise through favours (or, if you don’t get the chance, gifts): otherwise you will be looked as ungrateful.

Here is a Human saying, that now you could understand: «Friendships are born with a grazzje and die with a prɛgo».

Tributes

- Chinese Concepts of 生人 (shēngrén, literally “raw person”) and 熟人 (shóurén, literally “cooked person”).

- Cantonese Two different thank yous: a minor, 唔該 (m⁴goi¹), and a major, 多謝 (do¹ze⁶).

- English Pado derives from pardon.

- German Daŋke derives from danke (“thank you”) and bitte from bitte (“please”).

- Italian Grazzje derives from grazie (“thank you”), skuʃa from scusa (“sorry”), vore from per favore (“please”) and prɛgo from prego (“don’t mention it”).

- Japanese Dɔʃo derives from どうぞ (douzo, “please”).

Discussions

- Reddit: https://www.reddit.com/r/linguistics/comments/usblj8/when_did_it_become_widespread_in_european/